Breathing New Life into Techniques Rooted in Japanese Culture

2023.03.31

LIFE

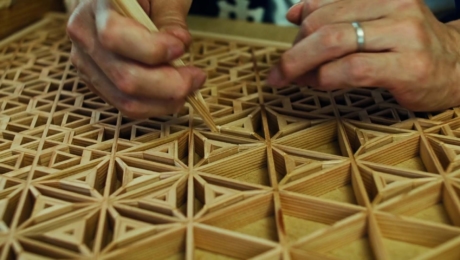

Kumiko woodcraft is made using intricate pieces of wood finished with a plane.

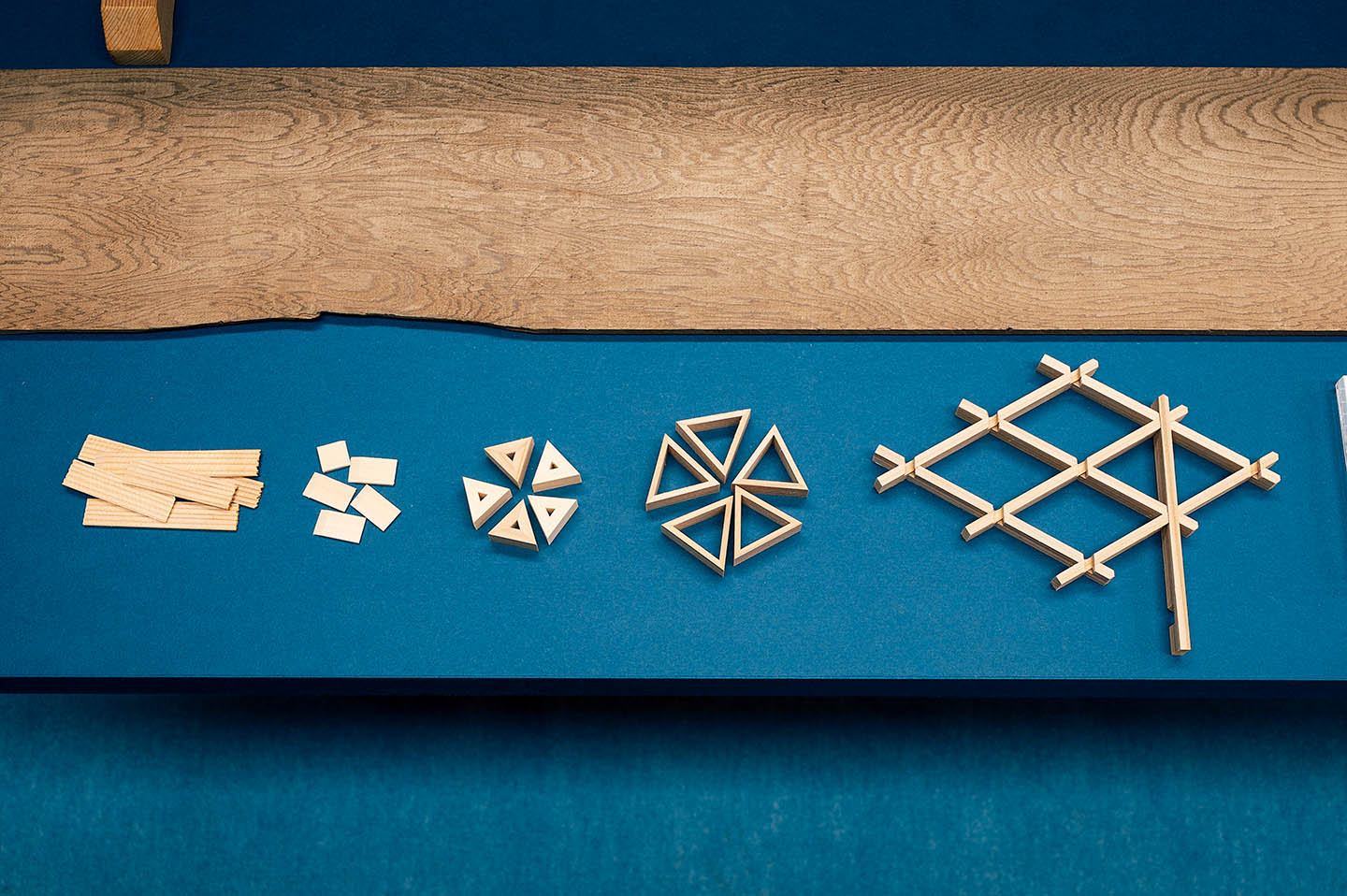

This craft was developed during the Edo period, when more precise crafting became possible thanks to evolutions in the techniques of joiners and improvements in the tool-making skills of blacksmiths. However, the roots of the craft are said to trace back to the joinery used in the Heian era (794 – 1185).

One of the doors of the Main Hall of the Horyuji Temple, which was constructed during the Asuka period (592 – 710), was made with a single piece of wood, one meter wide and two meters high, from a Japanese cypress tree over 1,000 years old. However, using large trees like this all the time would be impractical. This is what drove the evolution of joinery techniques, combining multiple smaller pieces.

This technique, rooted in Japanese culture, combines multiple pieces to reduce the amount of warping and bending. Many of the over 200 Kumiko woodcraft designs, such as plant patterns and snow crystals, reflect the varied faces of nature through the four seasons. Kumiko woodcraft has been passed on to modernity as a unique Japanese technique.

The first master of Tatematsu, Niigata Prefecture-born Matsuo Tanaka, began learning joinery at the age of 15. In 1982, he opened his own shop. The second master, Takahiro Tanaka, is a licensed first-class architect/building engineer. Over twenty years ago, he left the urban planning consulting company he worked at and began studying under Matsuo Tanaka.

Although he says that at the time he was simply carrying on the family business, and his decision had no deeper significance, Takahiro Tanaka says, “I found that, more than the urban planning work I was doing, which involved developing urban areas over decades, my personality was better suited to kumiko woodcraft, where I would listen to the requests of customers and apply all of my skills and knowledge to meet them. Seeing the smiles on the faces of my customers is an incomparable feeling and really fills me with joy.”

Demand for kumiko woodcraft has grown like never before, he says, but with respect to the future, he continues, “while things may be going well now, this tide will eventually pass. I’m not just making an empty gesture, talking about ‘preserving tradition.’ I also want to keep trying to create new things and polish my own abilities. Part of the reason I chose to take part in the Edo Tokyo Kirari Project is that I wanted to be exposed to new ideas that I had not encountered before.”

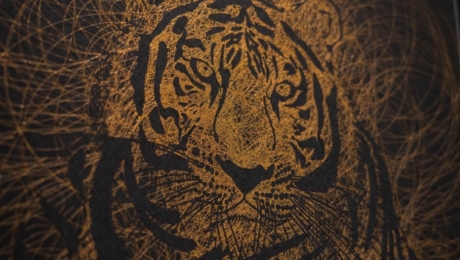

The patterns used in the collaboration, the kawari-asa-no-ha(double hemp leaf) and kikyo kikko (bellflower tortoise shell) patterns, both represent the warding off of evil. Layers of Noritaka Tatehana’s thundercloud motif are sandwiched between the layers of the kumiko woodcraft.

In his collaboration with Takahashi Kobo, Noritaka Tatehana created “Duality Paintings,” which express dualities like life and death or the sky and the earth in a single painting, in the medium of woodblock prints. In these kumiko woodcraft collaborations, he manipulates the viewer’s perspective using multiple layers, creating the duality of “that side and this side” in a single work.

“I think this is one of the handiworks I focused on most in this project,” says Noritaka Tatehana. “There was a lot that I didn’t know about how the work would turn out, but the kumiko woodcraft pattern combined well with the lightning motif, which also carries the meaning of ‘warding off evil,’ and the precise craftsmanship and bold painting, with its visible brush strokes, create a contrast that really stands out.”

These works were shown on the former site of the Saigyo-do, near the Kantoku-tei.

The Saigyo-do is believed to have been built during the reign of Tokugawa Yorifusa, the feudal lord that founded the Mito clan, and housed a wooden statue of the famed monk and poet Saigyo. However, in 1923, its pillars and roof collapsed during the Great Kanto Earthquake, and the wooden statue was lost in a fire. Although the building was reconstructed, it again burned down during the Second World War, and now all that remains are the stone foundation, a monument engraved with a waka poem written by Saigyo, and a pair of shishi lion statues that have withstood the ravages of time.

Trees surround the former site of the Saigyo-do, and beautiful sunlight spills through the canopy. The branches and leaves of the trees are reflected in the glass of the artworks, providing them with an ever-shifting countenance. Artworks are usually displayed where they will be unaffected by sunlight or the elements. One of the highlights of this exhibition is the way it showcases the allure of art by placing it in natural environs.

Photo by GION

Special Movie

Noritaka Tatehana x Edo Kumiko Tatematsu

NEXT: 新江戸染 丸久商店 / Shin Edozome Marukyu Shoten

https://en.edotokyokirari.jp/column/life/edotokyorethink2023-marukyu-shoten/